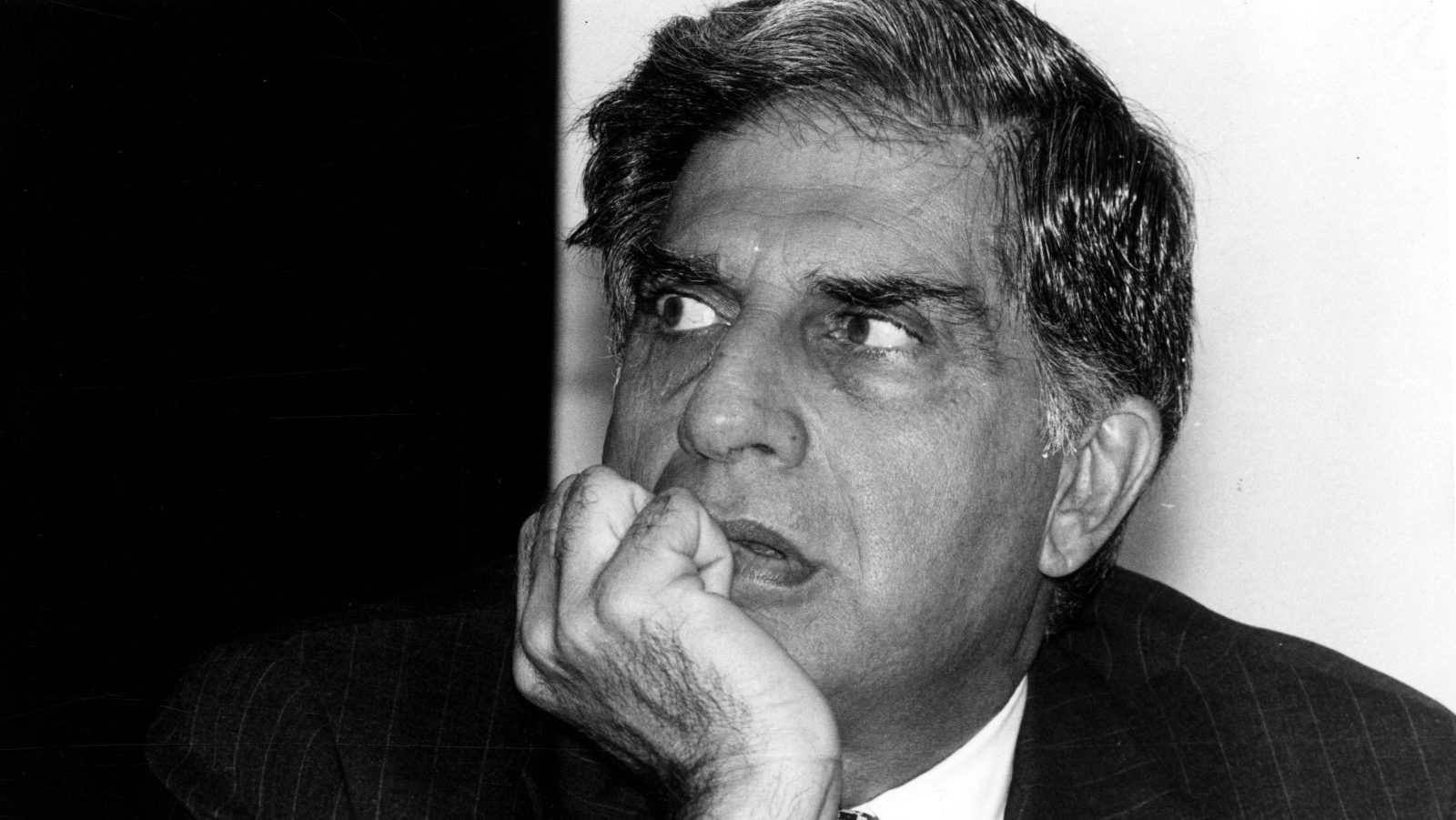

Ratan Tata was unquestionably India’s most respected businessman, even though by the standards of India’s wealthiest billionaires he was relatively poor. But by virtue of his position as chairperson of the Sir Dorab Tata Trust and the Sir Ratan Tata Trust, which own 66 per cent of Tata Sons, the holding company for India’s largest and most prestigious business house, he was more powerful than any other Indian businessman.

Despite perforce often being in the spotlight, the reclusive Parsi bachelor businessman was very much a loner and hard to fathom. His former executive assistant R Venkataraman, when asked about his proximity to his former boss in an unguarded moment, remarked that those closest to Ratan were not people but his pet dogs and all strays. In an interview with me, Tata did not entirely refute this characterisation confessing, “I am not very sociable but I am not anti-social”.

Ratan’s character was shaped to an extent by a lonely and strict childhood and a feeling of rejection. His father Naval was a disciplinarian. Ratan told me, “It was not that my brother Jimmy and I got caned, but he expected a certain decorum. We were never allowed to flaunt our wealth.’’ Ratan’s grandmother Lady Navajbai Tata, widow of Sir Jamsetji Tata’s younger son, was his main anchor when he was young. His mother Sooni left Ratan when he was only 10 and his father later remarried and had a second family. Navajbai ingrained in her grandson the unique industrial and philanthropic legacy of the Tata group, particularly the extraordinary history of the far-sighted founder Sir Jamsetji, who besides several other pioneering ventures, envisaged India’s first steel mill, first hydroelectric plant and the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore.

It was made clear to Ratan by his grandmother from a very early age that he had large shoes to fill. What is not known to many is that Ratan and his father Naval were not actually descended from the Tata founder. Neither of Jamseji’s two sons had children and after Ratanji’s death in 1918, his widow Navajbai adopted an orphan boy, Naval, from the J N Petit Parsi Orphanage in Parel, Mumbai.

It was Navajbai who insisted that Ratan return to India from the US after graduating from Cornell University in architecture and engineering Though his grandmother had full faith in Ratan, the top men at that time in the group, including the chairperson and distant relative JRD Tata, did not view him as future heir to the empire. If anything, when Ratan joined the group, the knives were out. He was posted in Jamshedpur, and moved from one department to another without any designation or clear-cut duties. “I thought they were testing me to see if I would throw in the towel,” he admitted.

JRD’s initial hostility towards Ratan was perhaps connected with the fact that he never got on with Naval and Ratan confesses he never dreamed at that stage of being his successor. Ratan admitted that he only got close to JRD in the older man’s last six years at Tata when the JRD began to revise his opinion about Ratan after the group’s fallout with Russi Mody. At 86, the legendary JRD stepped down as chairperson and Ratan at 51 was appointed in his place in 1991.

One of Ratan’s first acts as chairperson was to bring down the three satraps in the Tata empire, Russi Modi of the Steel division, Ajit Kerkar heading the Taj hotel chain and Darbari Seth in Tata Chemicals. The three ruled without permitting any interference from the Tata head office, Bombay House. Gradually from a shy, underconfident youth, whose credentials as a business executive were uninspiring, Ratan blossomed into a larger-than-life chairperson of the Tata group. He gave his group new visibility and prominence through a series of bold gambles. In 2000, he purchased the British Tetley; in 2007 he announced his intention to take over Europe’s second-largest steel manufacturer the hugely loss-making Corus; in 1998, Ratan, who had once produced the first indigenously built car, the Nano, acquired the luxury car brands, Jaguar and Land Rover. Some financial analysts have questioned Ratan’s business acumen in costly loss-making foreign acquisitions. A major reason for the Tata group to retain its pre-eminent position was the Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), which often bailed out Tata Sons and buffeted its losses. TCS contributed a major share of the group’s net profits for many years.

Jamsetji, the group’s founder, came from a pious Parsi priestly family in Navsari, Gujarat and set the benchmark for the family’s extraordinarily philanthropic spirit at the start of the 20th century. Apart from the Indian Institute of Science, institutions funded by the Tata trusts include the Tata Memorial Cancer Hospital, the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and the National Centre for Performing Arts. Jamsetji also set the tone for the group’s ethical business practices. The group’s leadership was for generations controlled by members of the tiny minority community, the Parsis, who pride themselves on their uprightness in doing business. During the era of the licence permit raj in the 1960s, JRD made clear that the Tata group was unwilling to pay politicians under the table even if it meant they would not be able to expand the capacity of their industries. For a while, the Tata group lost its first place to the Birla companies, but with changes in government policies, it soon recovered. Bombay House, the group’s headquarters, has the Zoroastrian philosophy, “Good Thoughts, Good Words and Good Deeds’’, inscribed as a reminder to all employees.

Ratan epitomised this Tata tradition, in both business and his personal life. His lifestyle was modest compared to India’s new billionaires. He had almost no security outside his home. His business exploits earned Ratan such adulatory titles as “India’s best brand ambassador” and “A model of corporate responsibility”. The two major Tata trusts are among the world’s largest philanthropic enterprises.

Despite an occasional whiff of scandal – such as leaked telephone taps suggesting that Tata executives were colluding with ULFA militants to secure their tea estates in Assam or the publishing of the Niira Radia tapes – nothing fundamentally dented Ratan’s pristine image. The only scandal which perhaps temporarily dimmed Ratan’s halo was his sacking of the chairperson of the group, the late Cyrus Mistry, in 2016. The calculated manoeuvres left the business world and the Parsi community shell-shocked. This was particularly because Mistry’s rebuttal letter before the National Company Law Tribunal accused Ratan of violating rules concerning insider information and handing out favourable deals to friends and a lack of transparency in corporate governance. Ratan, however, was vindicated in 2021 when the Supreme Court backed him on all issues raised by the Mistrys concerning the control of the group. Ratan also had the last laugh over sceptics questioning his business acumen. His choice of Natarajan Chandrasekaran to replace Mistry has paid dividends to the group.

The writer is contributing editor, The Indian Express