A recent Supreme Court judgment reveals the legal and ethical confusion surrounding euthanasia in India. A Ryles tube is a device through which food can be passed through the nose into the stomach. Permission to remove the tube was denied to parents of Harish Rana, a 32-year-old who has been in a vegetative state for the past 11 years with no chance of recovery. While withdrawal of life-support in cases deemed terminal is allowed in India as per the SC’s 2018 judgment, a bench headed by CJI DY Chandrachud observed on August 20, “Ryles tube is not a life support system.”

The term “passive euthanasia’, adopted by the Supreme Court in 2018, refers to allowing natural death by withholding or withdrawing life-prolonging measures in patients with terminal illnesses. This term is not ideal. Withholding of futile life-sustaining measures, or withdrawing them allows for natural death, while euthanasia implies an intent to kill.

Ventilators, drugs that force the heart to beat, and dialysis machines, indisputably come under the category of life-prolonging measures. However, clinically assisted nutrition and hydration — a term used to describe artificial feeding by any route other than the mouth, including the Ryles tube — is also a life support measure that can be withdrawn in the terminally ill. Besides the judgment’s medical validity, it is also crucial to question its ethical basis. Medical ethics has four broad pillars. First, “beneficence”, which makes it moral incumbent on the physician — or the bench, in this case — to act in the patient’s benefit. Second, “non-maleficence” makes it obligatory on the decision-maker to not harm the patient. Third, “justice” demands that the rights of the patient should not be exploited. Fourth, “autonomy” gives the patient the right to choose.

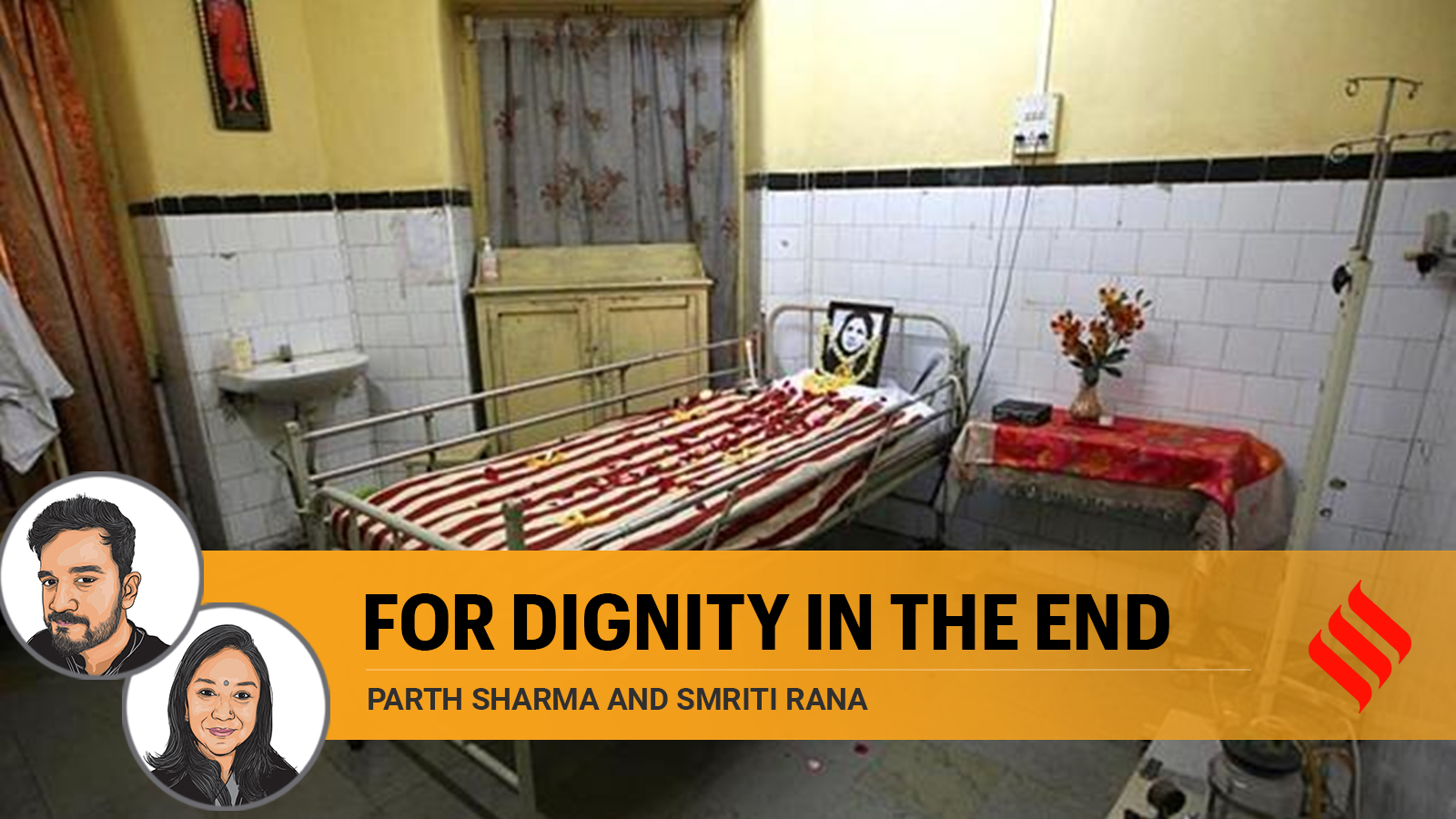

To prolong Harish’s life effectively does nothing but add to his suffering. His aging parents are financially destroyed and left without agency. It is hard to imagine what it must have taken them to arrive at this point when they moved court. It is hard to imagine what it must have taken his ageing parents to move court. The ethics of beneficence and nonmaleficence are evidently jeopardised. In addition, the right to a dignified life and dignified death has also been denied. The verdict, along with a similar judgment passed by the Delhi High Court in Harish’s case, raises serious concerns. Why are judges extending themselves to make medical decisions that they are not trained for? Why were palliative care physicians not consulted before arriving at this judgment? Why did the family have to go to court? Could the early involvement of palliative care physicians prevented their suffering?

The SC decision also reflects the general fear and negative impression of death and dying in our culture. Death from “passive euthanasia” in cases like these is interpreted as murder rather than liberation from prolonged suffering. As in many cultures, the act of feeding is not merely a function of survival but is conflated with care giving, hospitality, and love. Denying this is taboo at a social and existential level. Let’s try and understand the reality here, though. Living with a Ryles tube is painful. It is distressing to have it inserted, and then it must be changed every two to three weeks. Multiply this by 11 years. Imagine the state of the elderly parents who haven’t known where to draw the line between hope and wishful thinking.

The Honourable Court parenthesised the denial of permission to remove the Ryles tube with the idea that it would lead to death by starvation. We don’t know for sure if a person in a vegetative state would feel hunger in ways fully conscious people do, but we do know that extending life that is of such poor quality for both the patient and his caregivers is a travesty of medical ethics. Discussions around death and dying need to happen not just with people when they are unwell, but also within families during times of good health.

It is high time to bring legal clarity to the difference between euthanasia and the withdrawal of futile life-sustaining interventions in India by involving medical and ethical experts. Till such systemic gaps are addressed, it is important to educate ourselves about our rights and the options available to us by means such as Advance Care Planning and Advance Medical Directives which enable us to gain control over our last day. A good quality of life and death are everyone’s rights.

Sharma is a community physician and a public health researcher. Rana heads the WHO Collaborating Centre for Training and Policy on Access to Pain Relief. Both authors are members of The Advance Care Planning Task Force under the Indian Association for Palliative Care