Years ago, when I was posted in Kerala during the initial decades of my service, Wayanad was an idyllic hill station in the lush Western Ghats, known for its vast tea plantations. I had the opportunity to visit Wayanad several times and was always inspired by the warmth and resilience of the people. The origin point of rivers like the Kabini and Chaliyar, the district has dense forest cover. It is also home to various biological reserves, wildlife sanctuaries and national parks.

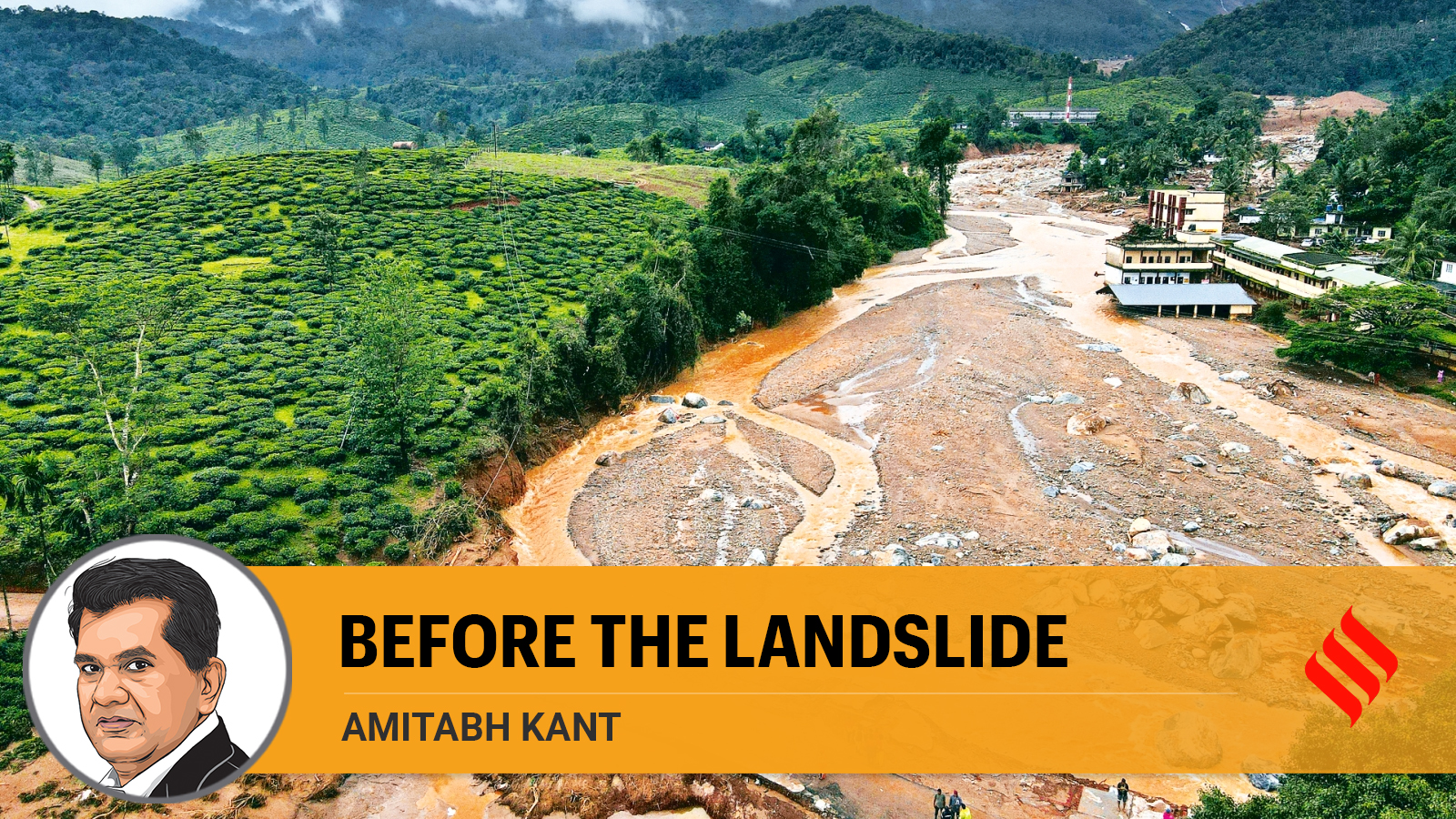

In the past few days, Wayanad has been in the news for a devastating landslide that claimed hundreds of lives. The landslide, which was triggered by a cloudburst, also resulted in the destruction of homes, with several people trapped under debris. It struck Meppadi, Mundakkai, and Chooralmala and resulted in the collapse of a nearby bridge that was used to enter Attamala in Mundakkai.

The disaster has left more than 300 people dead and over 300 are missing. While heavy rains caused the landslide, the unchecked development driven by tourism and quarrying has significantly disturbed Wayanad’s fragile topology.

According to climate experts, the landslide was triggered by extremely heavy rainfall caused by the warming of the Arabian Sea. The southeast Arabian Sea is becoming warmer, leading to atmospheric instability over large parts of the Western Ghat, including Kerala. Rain-laden areas with deep clouds are moving southward, resulting in excessive rain.

In 2011, the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel, headed by ecologist Madhav Gadgil, demarcated the region as an ecologically sensitive area (ESA). The Gadgil Committee recommended the banning of construction, mining, and quarrying activities in large parts of the Western Ghats, one of the world’s eight hottest biodiversity hotspots.

A similar tragedy struck Kerala’s hilly regions in 2019. Despite clear warnings from experts, unchecked construction and tourism-related activities have continued unabated. Wayanad, renowned for its scenic beauty, has become an eco-tourism hotspot, leading to rampant construction activities. Resorts have mushroomed, roads have been constructed, tunnels have been dug and quarrying activities have been undertaken without proper assessment of Wayanad’s carrying capacity.

Construction of roads and other infrastructure in such regions should be undertaken with scientific precision, keeping in mind the environmental impact. Unfortunately, the current practices lack these essential precautions, exacerbating the damage caused by landslides.

Nearly half of Kerala comprises hills and mountainous regions with slopes exceeding 20 degrees, making these areas particularly prone to landslides during heavy rains. Beyond making the state climate resilient, it is crucial to evaluate land use changes and development activities in landslide-prone areas. Landslides and flash floods often occur in regions where the impacts of both climate change and human intervention in land use are evident.

A 2022 study on depleting forests in Wayanad revealed that 62 per cent of the district’s green cover disappeared between 1950 and 2018, while plantation cover rose by around 1,800 per cent. The study, published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, indicated that around 85 per cent of Wayanad’s total area was under forest cover until the 1950s. Now, the region is known for its extensive rubber plantations. The intensity of the landslide increased because of the rubber trees, which are less effective in holding soil compared to the dense forest cover of pre-plantation times.

Mindless construction in vulnerable areas has greatly contributed to such disasters across the country, especially in hilly and mountainous zones. Experts have highlighted that extensive construction of roads and culverts in Kerala has not accounted for current rainfall patterns and intensities, relying instead on outdated data. There is a need to consider new risk factors in construction to prevent flash floods, as many structures fail to accommodate river flow, leading to significant destruction. Unscientific construction practices are a major cause of the current devastation.

The Western Ghats have been classified as an ecologically-fragile region. Recent research by experts at the Indian Institute of Science divided the 1.6 lakh sq km of Western Ghats into four ecologically-sensitive regions (ESR). Promoting sustainable land-management practices such as reforestation, controlled deforestation, and sustainable agriculture is crucial to maintaining hillside stability and reducing soil erosion, thereby mitigating the effects of heavy rains.

In 2018, devastating floods killed more than 400 people across Kerala, destroying homes, forested areas, and infrastructure. In 2020, 65 people, most of them tea plantation workers, were killed when a landslide struck Idukki district. A year later, landslides and floods claimed a high toll of lives in the district again. This time Kottayam was also hit. Landslips and flash floods struck again in 2022.

Kerala, once known for its lush greenery and beautiful monsoons, now faces tragedies caused by weather vagaries during these months. Over the past decade, the state has witnessed numerous climate-induced disasters, underscoring the urgent need for climate-resilient infrastructure.

The Wayanad tragedy is a stark reminder of the delicate balance between nature and human activity. It highlights the dire consequences of neglecting ecological warnings and the pressing need to adopt sustainable development practices to safeguard the environment and the lives that depend on it.

The writer is India’s G20 Sherpa and former CEO, NITI Aayog. Views expressed are personal