The first budget of the third term of the National Democratic Alliance reflected the changed political reality of the government but was far from the economic reality of the country. The change in political circumstances after the elections meant that the allies crucial for the government’s survival (read Bihar and Andhra Pradesh) found the necessary mention, but it was still short of what they expected. But a post-election budget was also an opportunity for the government to reset the fiscal paradigm to usher in a process of reforms for the economy still recovering from the slowdown of the first term and the pandemic-induced shocks of the second term. There is a consensus that despite the recovery, the economy is suffering from deficient demand, contributing to a slowdown in consumption growth, tepid private investment and precarious exports. In effect, all three sources of demand — private consumption, investment and exports — require a serious push for growth to be sustainable.

The reasons behind deficient demand are well-known. Most indicators of income and earnings in the last decade suggest either stagnation in real earnings or, worse, decline. According to the Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS), real earnings of regular workers have been declining since 2011-12. Labour Bureau data on wages shows a decline in real wages in non-farm occupations, with agricultural wages almost stagnant. Recent reports on the unorganised sector also suggest a decline in real earnings. Cultivation incomes have barely increased by 1 per cent per annum in the last decade. Together, these account for almost three-fourths of workers in the economy. The only remit for this budget should have been to find ways to raise the earnings of these workers. In reality, there is not even a recognition of the crisis of earnings in the economy. The rural economy has been in distress for almost a decade. It has now spilled over to urban areas. Depleting household savings and non-collateralised retail loans are fuelling whatever little consumption growth is visible.

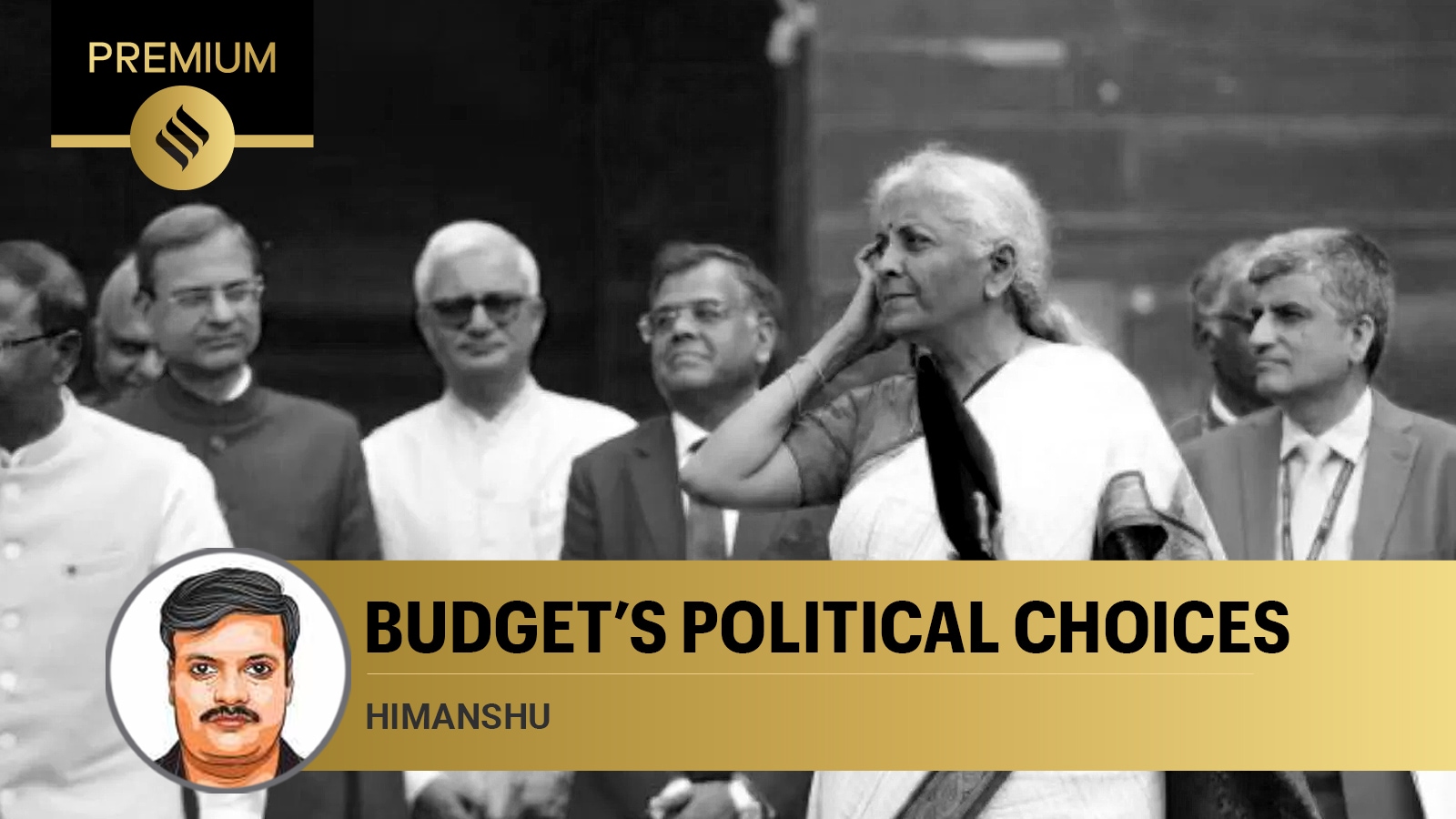

The Finance Minister did not have to look for solutions. Its own Economic Survey argues for the necessity of agricultural growth for sustained economic revival. The budget has announced a wish list without allocating anything additional for agriculture. The idea of encouraging natural farming was announced first in the 2019-20 Budget. The actual spending on National Mission on Natural Farming last year was Rs 100 crore even though the allocation was Rs 459 crore. This year, even this has been reduced to Rs 366 crore. The total budget allocated for all agricultural research institutes, including ICAR and NAAS, and agricultural universities has declined compared to last year. Of the eight schemes as part of the first priority of ‘Productivity and Resilience in Agriculture’, none has seen an increase in budgetary allocation. While fertiliser and food subsidies have seen lower allocations, even the PM-KISAN has not seen any increase in yearly transfers since 2019. For the broader rural economy too, there is hardly any increase in allocations. The lifeline during the COVID pandemic and the slowdown, MGNREGA, has seen a decline, compared to the actual spending in 2022-23, and the same as last year’s revised spending. Given the important role it plays in raising rural wages, it could have been the instrument to improve incomes in rural areas.

While the Economic Survey has blamed the private sector for being ungrateful for not contributing to raising private investment, the budget has done little to enthuse them. The flawed approach of a supply-side response with massive corporate tax cuts in 2019 has not led to a private-sector investment revival. However, the private sector used the subsidy to clean its balance sheet without contributing to increasing investment or generating employment. But blaming the private sector is hardly the solution. The real elephant in the room is a lack of demand with no corporations willing to invest so long as demand remains subdued. The solution does not lie in incentives and subsidies to the corporate sector but in creating demand in the economy.

Perhaps, as punishment, now the private sector has also been asked to shoulder the burden of creating jobs in the economy. With the lack of decent employment becoming a political issue, this budget has proposed a plan of Rs 2 lakh crore to be spent in six years to create 41 million jobs. However, the outgo in the current year is only Rs 28,000 crore for the employment incentive schemes and even this is unlikely to be spent given the onerous conditions set out for getting the benefit. All three incentive schemes require workers and enterprises to be part of EPFO. The total number of workers registered in EPFO was 13 million in 2023-24, one million less than in 2022-23, despite several schemes on similar lines already in place since the pandemic. The government now intends to create 16 million EPFO-enrolled jobs this year with a government cost of Rs 17,500 per employee. The rest of the employee cost is to be borne by the private sector. Even with an average salary of Rs 25,000 per month (the schemes are for employees earning less than 1 lakh per month), the private sector will bear 94 per cent of the new employee cost.

The reality of how much was actually spent and how many jobs created will be known only next year when a new set of announcements comes. With actual spending in most departments remaining below-budgeted expenditure every year, budget announcements look more like political manifestos than actual action plans. But any concrete action to revive demand and investment in the economy requires changing the political-economy paradigm, which still favours supply-side incentives when the problem is a lack of demand due to stagnant or declining incomes. It is a political-economy approach that prefers large subsidies to corporates as essential even if it is at the cost of pruning investment in agriculture, rural development and human capital. The problem is also not of fiscal prudence but of political priorities — of where to spend. In the end, a budget is a political choice not just an accounting exercise.

The writer is associate professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, JNU, New Delhi