Dear Readers

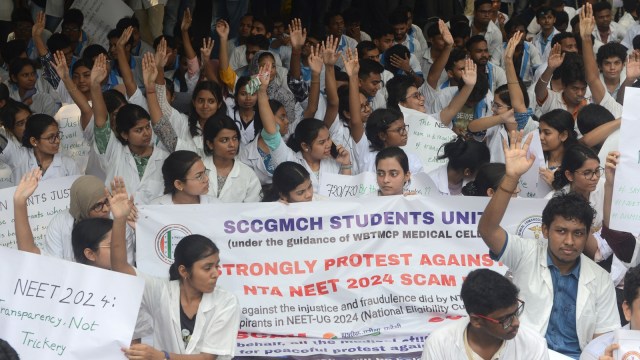

In less than five days, the government has cancelled one examination, postponed another two and removed the head of the agency which conducts entrance tests to higher education institutions. Meanwhile, the controversy over the results of the entry-level tests to undergraduate medical courses rages on. By all accounts, the impasse created by the government’s decisions last week has added to the insecurities of a large section of students.

The entrance examination system, whether those pertaining to educational institutions or public recruitment, has been long roiled by controversies. The developments since the beginning of June are no aberrations. The government has appointed a committee to suggest measures to make the system foolproof. This is a long overdue measure. The diversity quotient of the group of youngsters who appear for public examinations has been constantly increasing. This growth of the aspirational class augurs well for democracy. But when young people who had studied hard for an examination find their efforts frustrated by a system that cannot check leaks and malpractices, it leads to frustration and a loss of trust. The panel has to find ways to restore this trust.

Hyper competition

Chinks in the examination system are, however, only a part of the problem. A major reason for the examinations becoming hypercompetitive is the shortage of opportunities for the expanding aspirational class – whether that be in educational institutions or employment avenues. This year 24 lakh students appeared for entry to a little more than 1 lakh undergraduate medical seats.

Of course, society also attaches an irrational premium to medical and engineering courses – and government colleges. Perhaps that’s also the reason for the desperate exodus of students to areas that present difficult challenges – countries that comprised the former Soviet Union, for instance. And, perhaps that’s why the parent of a student who couldn’t make it to a competitive test in time fainted outside the examination centre, last week.

There is, however, another way of looking at things. The preference for medical and engineering – as well as government jobs – is a sign that the basket of opportunities doesn’t cater adequately to the demands of people. The number of government jobs has stagnated for at least a decade and the increase in the number of institutions that provide good education at affordable costs hasn’t kept pace with demand. A study published last year by the Azim Premji University’s Centre for Sustainable Employment said that unemployment among graduates under the age of 25 was at 42.3 per cent in 2021-’22.

All this creates conditions for the job and examination mafia to thrive. Lakhs of students spend their best years enrolled in coaching classes that do nothing other than teach rote learning techniques. Needless to say, this demand supply gap hurts the disadvantaged – in terms of caste, class, gender, geography – the most.

Myriad approaches

India is a young country. But the existence of a young, large working age population does not ipso facto translate into a demographic dividend. This population should not just be a part of the labour force, but productively employed in jobs that cater to their aspirations. A country with a young population with unfulfilled aspirations does not speak well of the powers that be.

India still has about 20 years to reap its demographic dividend. But by the time this government ends its tenure the best years to gain this advantage would have almost passed.

Unravelling the examination mess, then is primarily about creating a larger pool – of jobs, education – and enhancing skills. Incremental measures will not be enough, but at the same time the government should take special care that historical disadvantages are not aggravated. In a country of myriad diversities, a one-size fits approach to fulfilling the aspirations of youngsters and ensuring a creative workforce may not be right. This imperative would require the government to listen to all voices – even those that might ostensibly seem dissenting. The Opposition, with its significantly added presence, will also need to do more than engage in politics of disruption.

The overwhelming onus, though, will be up to the government to do things differently.

Till next time

Kaushik Das Gupta