The Minister for Law and Justice has just announced a National Litigation Policy. He said it is aimed at “transforming the government into an efficient and responsible government”. The policy, he is reported to have said, is intended to reduce high legal costs and decrease the number of cases in which the government is a party as well as the load on the courts. At the same time, the Home Minister has said that three new criminal laws will be brought into force with effect from July 1, 2024.

At the heart of every criminal law is the need for its compliance with criminal procedure. This is for the reason that criminal law has the potential to result in the deprivation of life and liberty of the citizens. Article 21 states that no person shall be deprived of life and liberty except by procedure established by law. The procedure established by law referred to here is the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), which has now been abandoned and replaced by the three new criminal laws. The Indian Penal Code defines substantive crimes and tells us what behaviour is criminal and what is not. This too has been reworded and replaced and new crimes have been created. What are the implications of this for the citizen who may find herself an accused in a criminal case? Will the three new laws reduce legal cost and save court time as intended by the National Litigation Policy or increase the burden of costs on the accused and the burden of backlog on the courts?

In every criminal case, it is the state itself, which brings the case against an accused and is a litigant before the court. The three new criminal laws reword almost every section of the three fundamental criminal laws, the IPC, the CrPC and the Indian Evidence Act. These laws have been in operation for over a century and have received interpretations at the hand of the Supreme Court of India. Predictability and certainty of criminal laws is one of the fundamental principles of the rule of law. People base their conduct on laws in existence and modulate their conduct to avoid criminality. When there is uncertainty about criminal laws, the life and liberty of citizens is in grave danger as the consequence of violation of criminal laws is arrest.

With effect from July 1, unless stopped, we will have two different systems of criminal justice in operation. Substantive laws cannot be retrospective; procedural laws can be unless they negatively impact the accused. Now, in every case it may be argued that the new procedure negatively impacts the accused and these disputes will take their own time reaching the Supreme Court. Until then, we will all live with a sense of uncertainty about our right to life and liberty, not knowing which law governs us.

All this will add to the burden of an already overburdened judiciary leading to interminable delays. No audit has been done of the likely impact of three new criminal laws on the delay that will be caused or the infrastructure needed to upgrade the system of delivery of criminal justice.

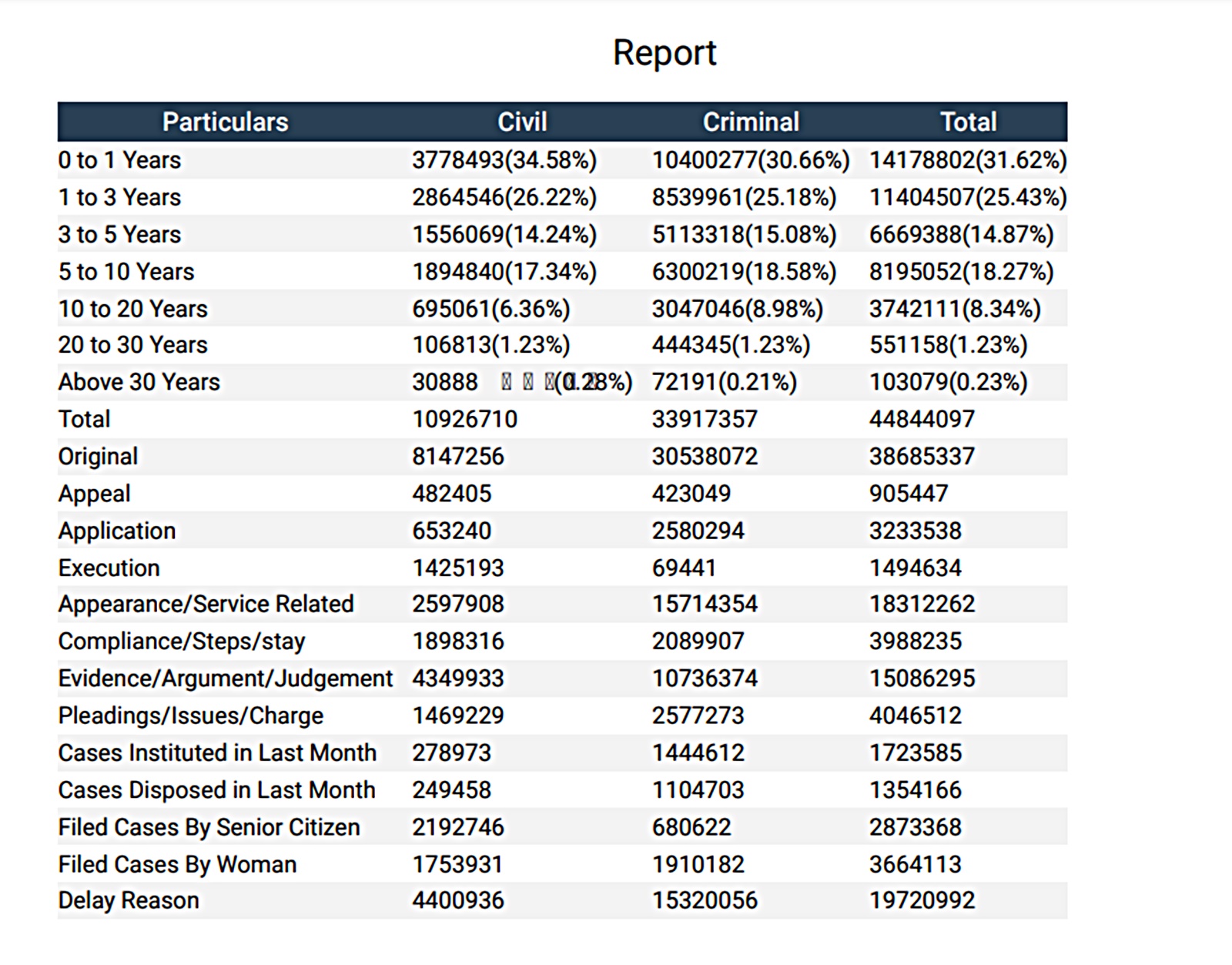

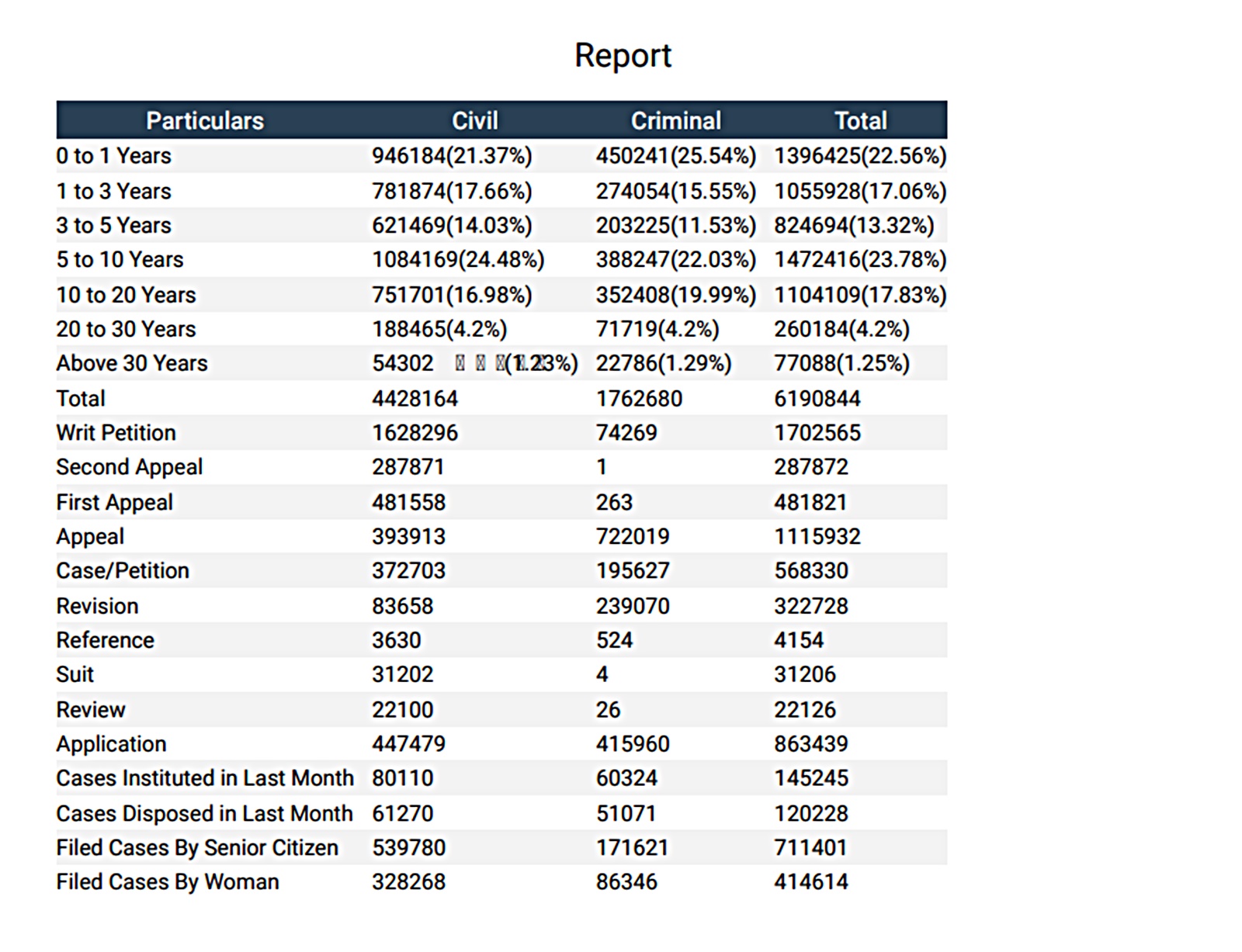

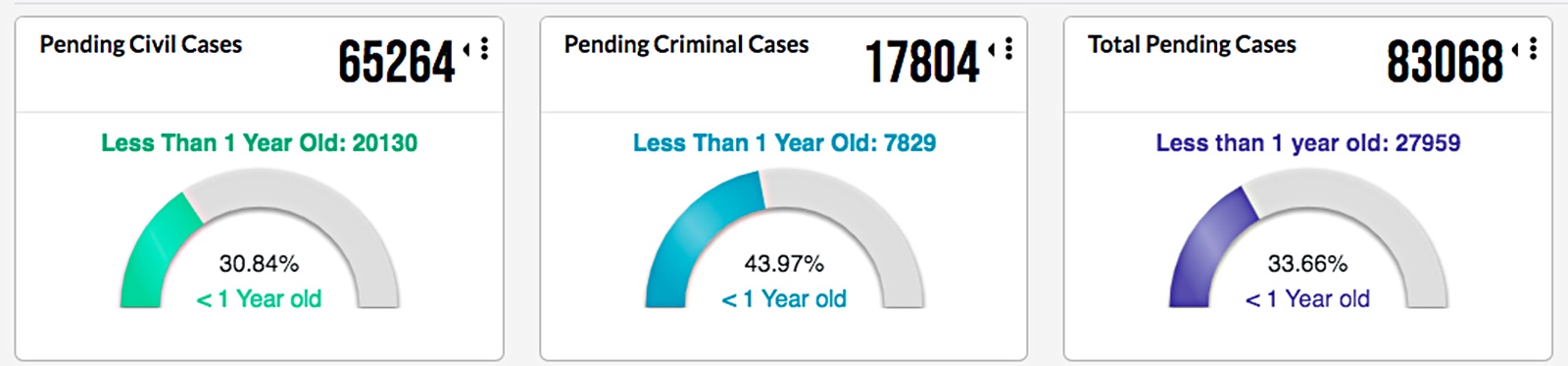

The National Judicial Data Grid shows the galloping pendency of criminal cases across all the courts in India — over 83,000 cases overall. This backlog will only increase by an estimated 30 per cent, leading to a virtual denial of access to justice.

In addition to the burden of costs and backlog, there are the questions of the creation of several new offences which will impact our life and liberty. Notwithstanding the fact that section 124A of the IPC which defines sedition is challenged and stayed by the Supreme Court of India, it has been repackaged in a more virulent form and enacted in the new criminal law. (See: Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act, 2023). While the earlier law made no reference to the sovereignty and integrity of India, the new law introduces this as an offence for the first time in the revised Indian Penal Code (BNS). The result as we have seen is that an ordinary riot can be elevated to the level of an attack on the sovereignty and integrity of India.

The Supreme Court in Lalita Kumari vs Government of Uttar Pradesh (2013) held that a First Information Report (FIR) must be lodged if a cognisable offence is disclosed. Only in certain rare cases where there is a possibility of mala-fide intentions of the complainant or commercial rivalry is suspected, a preliminary inquiry is conducted before lodging the FIR.

The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 mandates a preliminary inquiry in every cognisable offence which is made punishable for three years or more but less than seven years. (See: Section 173(3)of BNSS) This shows scant respect for judgments of the Supreme Court and heralds an era in which the liberties protected by the Court can be overridden by the legislature.

Provisions of the UAPA, an Act which is stringent enough, negating the rights of the accused, has been incorporated in the new law. Sections 15, 16, 17, 18, 18A, 18B, 19, 20 of the UAPA which deal with terrorist act, punishment for raising funds for terrorist act, punishment for recruiting persons for terrorist act, etc., have been incorporated by and large in Section 113 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Act, 2023.

This will make it possible to be prosecuted for the same offence under two different laws by two different agencies — the NIA and the local police of the state. These developments herald the beginning of an era in which our hard-won rights guaranteed by the Supreme Court of India can be undone in Parliament by a government which has the numbers to govern.

With the announcement of the National Litigation Policy, the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, and Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023 ought not to come into force on July 1 and until we are guaranteed speedy access to justice through a judicial audit of these laws, on the extent to which the backlog of criminal litigation will increase and the impact of these laws on fundamental rights of the accused.

The writer is senior advocate, Supreme Court and trustee, Lawyers Collective