Supporters wear Modi masks during a BJP rally in Meerut. File | Photo Credit: Reuters

The 2024 Lok Sabha elections were unique. The verdict shows that the voters prefer to have a delicate yet politically viable balance. The BJP-led NDA emerged as the leading formation, while a strong and effective Opposition also came into existence for the first time in last 10 years. This seemingly fragmented political configuration cannot be understood without a careful analysis of caste and community-based electoral responses. The CSDS-Lokniti post-poll survey highlights three trends in this regard.

Subaltern reach

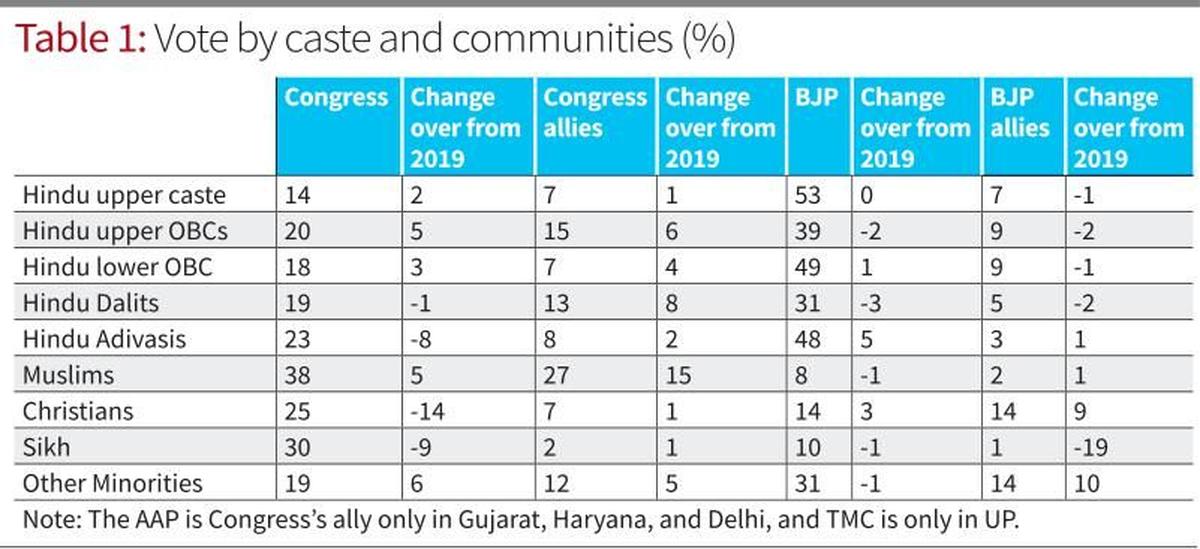

First, the BJP somehow managed to protect its carefully nurtured constituency of voters — upper caste Hindus, OBCs, and Adivasis; as well as Dalits on a somewhat lower scale. However, a slight movement of these social groups towards the Opposition weakened the party’s prospects in some key States such as Uttar Pradesh. For instance, the Hindu upper caste continued to support the party, though a small fraction also moved towards the Opposition. The Hindu OBCs (especially the “lower” OBCs) and the Hindu Adivasi voters overwhelmingly supported the BJP. This shows that the Hindutva-driven subaltern outreach of the party at the grassroots level worked well nationally. We also cannot underestimate the significance of the Labharati phenomenon: the welfare schemes introduced by the BJP were well-received and created a favourable electoral ground for it.

Diversity in Dalit vote

Second, Dalit voters played a crucial role in this election. The BJP received 31% of Dalit votes at the all-India level. However, Dalits also voted for the Congress and its allies in key areas. This apparent diversity of Dalit electoral behaviour in this election underlines an important political trajectory. The BJP’s slogan of “Ab Ki Baar, 400 Paar (this time, we will get 400 seats)” created an impression among the poor Dalit communities that the party might make significant changes to the Constitution. This impression was carefully used by the Opposition during its campaign. The Congress manifesto recognised the protection of the Constitution as an electoral issue. In fact, Congress leaders worked hard to use the Constitution as a political symbol. This overtly Constitution-centric politics sensitised a segment of Dalit voters. The BJP’s attempt to communalise the reservation debate failed to attract additional Dalit votes.

Minority vote

Third, the religious minorities — Muslims, Christans, and Sikhs — did not get behind the BJP this time. This was because the party changed the meaning of its slogan, “Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas (together with all, development for all)”. The BJP manifesto did not have any programme for religious minorities. During the campaign, BJP leaders tried hard to polarise voters on religious lines. Even affirmative action policies were problematised to create the perception that the Congress wanted to give undue reservation to Muslim OBCs. This anti-minority rhetoric encouraged the minority communities to support non-BJP formations at the State level.

This support, however, cannot be called vote bank politics. The voting pattern of religious minorities proves this point. While more than 65% of Muslim voters supported the Congress and its allies, it is also true that almost 8% of Muslims voted for the BJP in this polarised election and a large share of Muslims voted for ‘others’. The BJP also secured 10% of the Sikh and 14% of the Christian votes, respectively.

Hilal Ahmed is associate professor at CSDS