NEW DELHI: From the banks of Ganga in Anupshahr to the bridge over Yamuna near Chhaprauli; the sugarcane fields of Baghpat and potato farms in Khandauli near Agra to the hing (asafoetida) shops of Hathras; the Dalit enclaves of Agra to the rural population of Gautam Budh Nagar, the rippling proModi wave that was pretty much visible in 2014 and 2019 is not that evident this time round in

western Uttar Pradesh

.

Unlike the presidential nature of the last two elections — with PM Narendra Modi’s persona and national issues taking centre stage — this time, local factors and candidates seem to be making a comeback.

“I am voting for S P Singh Baghel (

BJP candidate

) and not the party,” said Ram Hari Pradhan from Parbatpur village near Khandauli in Agra, a region famous for its potatoes. Like most others in the region, Pradhan continues to use the name although he no longer holds the panchayat post. “I may not have voted for BJP if Baghel was not the candidate,” he added, citing his personal equation with the candidate who started his career with SP, then switched to BSP and finally to BJP.

“This time, there might be a split in Jat votes as the youngsters are angry because of the Agniveer scheme. Look at unemployment and inflation. The govt has not fulfilled many promises,” added Pradhan, a Jat. In the last two elections, Jats overwhelmingly voted for BJP. Pradhan, a retired Army man who is now a potato farmer, has two sons serving in the forces. “In my village, more than 50 families have retired as or are serving military personnel. Young people are heartbroken because of Agniveer while Jatavs of my village may vote for SP candidate. BJP may still win but with a lower margin,” he added.

“Earlier, at this time of the day, you would have seen many boys running on this road (training for Army recruitment). They have now lost interest,” added Ravindra Kumar Baghel from Ujari Jat village. Baghel is a community of shepherds whose traditional work is raising goats and sheep. “S P Singh Baghel is the tallest leader of the community and our votes are united for him,” he added.

Muslim votes will go to INDIA grouping, said Chaman Usmani, a street vendor at Tedi Bagiya in Agra. The area, with many posters of Ambedkar, has a significant Jatav population. “Jatav vote is splitting this time,” said Pappu, a Jatav who works as a fruit vendor at Tedi Bagiya. “The community is still assessing which candidate will defeat BJP and will vote accordingly,” he added. “This time both SP and BSP’s candidates are Jatavs and the votes will get split.” Despite a significant Dalit presence, BSP has never won this parliamentary seat.

Before delimitation, Raj Babbar won the Agra seat on SP’s ticket in 2004 and 2009. Since then, the seat has gone to BJP as Muslims moved towards SP and Jatavs towards BSP, giving the saffron party an advantage. “This time, both BSP and SP are in a contention in this seat,” said Hari Bhai, a former councillor of Agra Nagar Nigam (municipal corporation) and a BSP member. “Some Jatav votes can go to SP because of the candidate’s image,” he added.

Neighbouring Hathras is considered a saffron stronghold where the party has lost only once (in 2009) since 1991. The district was an industrial hub during the British era and is famous for its asafoetida and desi ghee production. It is also the hometown of satirist Kaka Hathrasi. “BJP seems to have an advantage in this seat. Despite the visibly lower enthusiasm among its cadre, the saffron party will scrape through because of a weak opposition but the margin could be lower,” said Raj Deep Tomar, who runs a local digital news platform.

Tomar said the RLD alliance stopped Jats from completely shifting away from BJP. “There is, however, a divide in the community — the older generation will vote for BJP while the youngsters, upset with Agniveer, may gravitate towards SP,” he added.

Tomar claimed that people in the region were gradually moving away from mainstream TV news channels because these hardly highlighted local issues. “There’s a fatigue over repetitive stories being carried by the big channels. Drinking water is a big issue in the area around Hasayan block on Junction-Sikandra Rao road. It hardly gets reported.”

“Even a lamp post will win the election in Hathras on a BJP ticket,” said Sanjeev Kumar of Bahanpur village, who is a farmer and transporter. A Sengar (Rajput) by caste, Kumar has never voted for any other party. “There are more than 80 Sengar villages on this road and they all vote for BJP,” said Mohan Murari of Nagla Tanja village. Similar thoughts were echoed by Om Vir Singh of Sathiya village. “My vote is for BJP and not Modi,” added Kumar. “This govt’s policy favours the super-rich but people don’t understand that.” Asked about his source of information, Kumar said, “I watched it on YouTube. I haven’t watched TV for over a year.”

In the first phase on April 19, similar sentiments were reflected in Baghpat, where many RLD

voters

had said that they were voting for NDA because of RLD and were not happy with many govt policies, including the Agniveer scheme.

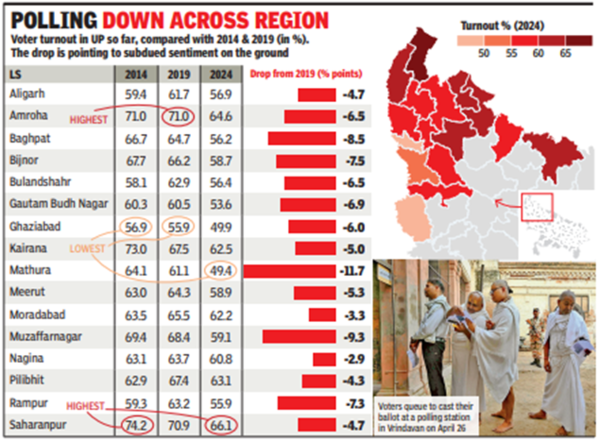

Poll statistics often don’t tell the whole story. But there was a big jump in polling percentages in 2014 and 2019, when a Modi wave was discernible in the region. This time, in the first two phases in Uttar Pradesh, every single constituency saw a drop in polling as compared with 2019 — ranging from 11.7 percentage points in Mathura to 2.9 percentage points in Nagina (see graphic). This, as well as the diverse voices on the ground, is indicative of a waveless election.