Nomadic and pastoral ways of life shaped human civilization. In Africa alone, livestock production accounts for at least 25% of their GDP, supporting over 26 crore pastoralists. In India, nomadic pastoral tribes like Baghels, Gadariyas, Gaddis, Bakarwals, Gujjars, Maldharis, Kurubas, Konars, Monpas and Dhangars of Maharashtra constitute around 1.3 crore (nearly 1%) of the population. Today, the Dhangars are struggling to maintain their ancient ways of life and be responsive to the current social and political challenges.

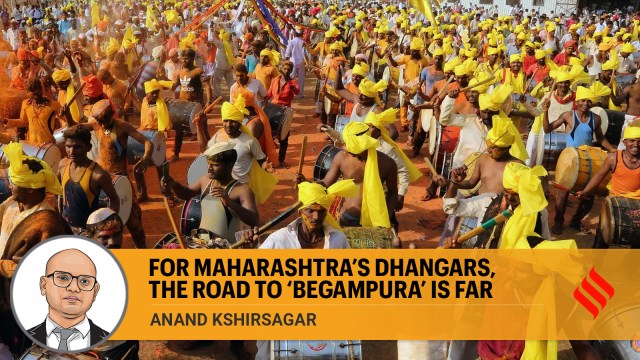

The Dhangar (shepherd) community is on the Vimukta Jati and Nomadic Tribes (VJNT) list in Maharashtra. On the Central list of Other Backward Classes (OBC), the community has been listed as “Dhangad”. Constituting nearly 9% of Maharashtra’s population, the Dhangars practice both nomadic pastoral, and semi-nomadic and agrarian lifestyles in rural areas. The nomadic community from the Hindu fold derives its social and cultural lineage from indigenous Bahujan folk traditions, and deities like Khandoba, Biroba, Pandurang, Jyotiba, Banubai, Mahalsa, Tulja Bhavani and Mandhardevi.

The struggle for political presence

Effects of caste-based social, economic and cultural marginalisation of Dhangars can be seen in their poor performance on human development index indicators. On the economic front, drastic changes such as conversion of agricultural land for non-agricultural use, and reduction in gairan (common pasture land), devrai (community sacred groves), community water bodies, forest cover, etc., have created a complex set of political, economic and social challenges for them in Maharashtra. Since most agricultural land in the state is predominantly owned by the upper caste, the Dhangars can neither unleash their true economic potential in rural areas, nor get a quality education needed to flourish in service and manufacturing sectors in urban areas.

Nomadic pastoral tribes have also struggled to maintain their political presence at both the local and national levels. Despite leaders like Karnataka CM Siddaramaiah from the Kuruba (shepherd) community and new Dhangar faces in Maharashtra politics, such as Ram Shinde and Gopichand Padalkar (both BJP) and Sakshna Salgar (NCP-Sharad Pawar), the community’s culture, social narratives and rituals are in danger of being co-opted by due to Brahmanisation.

This process robs the Dhangars of the organic process of social memory-making, which involves developing, preserving and transferring their independent cultural, historical and social narratives to the next generation. Brahmanisation and Sanskritisation of the Bahujan Varkari Bhakti tradition poses the most potent danger to the social and cultural memory of all Bahujan castes in Maharashtra.

Recently, the hagiography of historical figures like Ahilyabai Holkar and Yashwant Rao Holkar was used in an attempt to develop a martial (Kshatriya) identity among Dhangar youth. This was done by the community trying to make Chondi village in Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar district as a social and cultural rallying point. The name of Ahmednagar district was also changed to Ahilyanagar to galvanise the collective Dhangar identity.

Today, Maharashtra’s Dhangar leaders like Mahadeo Jankar of RSP are trying to develop an independent political rallying point for the community. However, many Dhangar political activists are unaware of the immense contribution of BSP’s Kanshi Ram and organisations like BAMCEF in mobilising, nurturing and training leaders like Jankar.

Without a clear understanding of such historical, social and political memories of the community and their interrelation with the broader Bahujan liberation movement, the Dhangars will always be vulnerable to political manipulations like the MADHAV (Mali-Dhangar-Vanjari) political engineering to consolidate OBC votes.

Why national-level caste census is needed

The recent recommendations by the Justice Rohini Commission on sub-categories within OBCs and the Dhangar community’s demand for a Scheduled Tribe (ST) status in Maharashtra could shape the political trajectories of the communities — and the broader Bahujan communities — in the state. In absence of national-level caste census data on social, educational and economic indicators of nomadic and pastoral communities, such recommendations and demands are bound to intensify political and social confusion within the community.

Psalm 23 of the Bible says, “Lord is my shepherd.” It imagines the creator of the universe through the beautiful analogy of a compassionate and wise shepherd who cares for his innocent herd and guides it to the promised land of ‘Begampura’ (Bhakti poet Guru Ravidas’s idea of an equal world without sorrow, exploitation, humiliation and discrimination).

Have the shepherd communities in India reached Begampura? I am not convinced. But the collective consciousness developed from a combination of independent social memory and data-driven policymaking from national-level caste census data could be the first step in that direction.

Anand Kshirsagar is a Harris Merit Scholar studying Master of Public Policy at Harris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago

Suraj Yengde, author of ‘Caste Matters’, curates Dalitality, has returned to Harvard University