Within the first few minutes of Laapataa Ladies, a young bride trips and nearly falls — clearly not yet used to wearing a veil that covers her face and therefore, her eyes. Her stumbling, though, seems to worry no one. An older woman promptly slips in a comment: “Ek baar ghoonghat le liya toh aage nahi, neeche dekh ke chalna seekho” (“Once you’ve worn the veil, you better learn to walk looking down, not ahead”.)

Kiran Rao’s second film as director, coming a full 14 years after 2010’s Dhobi Ghat, is a tapestry of such ‘homespun’ truths. In any society, idioms either issue warnings against common misfortune or help people deal with misfortunes they might have failed to avoid. Idioms and sayings are crucial in laying out the social setting of Laapataa Ladies: The fictional Hindi-belt state of Nirmal Pradesh, around 2001. As the just-wedded Phool Kumari (Nitanshi Goel) sets out for her new home, her young husband Deepak (Sparsh Shrivastav) advises her to take off her gold jewellery to be safe. “Jevar chori, do dukh paana. Chhota dukh chori, bada dukh thaana,” (“Being robbed of jewellery makes one sad, but the police station makes one sadder.”) he proclaims. Visiting a police thaana is worse than being robbed. The experience of police malfeasance is lodged so deep in the veins of North Indian life that it is now folk wisdom.

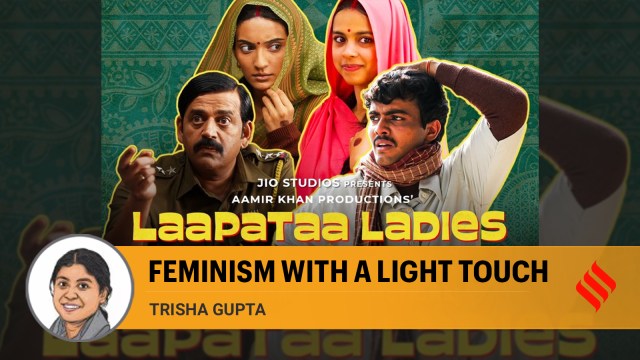

What makes Laapataa Ladies stand out?

What makes Rao’s script rare for mainstream Bollywood, though, is her attempt to take viewers from this sort of wisdom, offering commentary on an unjust world, to the sort that can see beyond it. The film’s embodiment of the latter is Manju Maai (Chhaya Kadam), at whose tea stall the lost Phool finds herself, literally and metaphorically. Like the older women in Phool’s family, Maai has seen life. But unlike them, she’s not blinkered by the domestic.

For the sheltered young woman (like the sheltered schoolboy protagonist of Gulzar’s 1977 classic Kitaab), four days at the railway station are a crash course in worldliness. Learning to trust the young men who give her shelter, or discovering that her skills can earn her money are revelations for Phool, as for most Indian women brought up to blindly trust men in their own family while distrusting every man (or woman) outside it. Maai’s words offer the necessary corrective to that social brainwashing, remaining humorous in tone but almost clunkily feminist in content — joking about the large-scale “firaad” that tells women they’re dependent on men, or suggesting that a suhaagraat and a stash of jewellery might be all her husband wanted from the wedding.

Shaadis and movies

Maai may be wrong about Deepak, but she’s right about there being something very wrong with Indian matrimony. Shaadis have long been a favourite setting for popular films, pressing some invisible feel-good button on the Indian psyche. More recently, though, some creators are going behind the glitter to reveal their dark side: The longlisting of social ills in two seasons of Made in Heaven (2019, 2023), or the sad marital frauds in Tanuja Chandra’s reality-based series Wedding.con (2023).

These new narratives, though, are largely urban and realist. And while our melodramas used to show the poverty-stricken fathers of daughters being made to stoop low by the greedy fathers of sons, those tragedies offered no justice. In a world where we all know that bride-takers gloat and bride-givers suffer, where a daughter’s marriage is assumed to be a crippling expense, tragedy can only be accepted. It takes comedy for everyday villains to get their comeuppance.

Yet comedy about serious things is rare, on-screen as in life. In the few instances when heroines have turned tricksters to teach dowry-seeking bridegrooms a lesson, Sonam Kapoor in Dolly ki Doli (2015) and Parineeti Chopra in Daawat-e-Ishq (2015), the films failed at the box office. Consumerist greed is so normalised in post-liberalisation India that no one bats an eye at the transactional nature of marital negotiations. Even nice guys assume dowry is their due. In 2020’s Panchayat, among the most subtly funny OTT shows we’ve had in a while, the men in a UP village calculate what demands are ‘appropriate’ for their salaries. The show’s urban protagonist Abhishek (Jitendra Kumar) declares he won’t take dowry, but the system is all around him. When a visiting groom demands Abhishek’s new swivel chair, Abhishek has to bend with the bride-givers.

That cartoonish spoilt-child dulha is one ridiculous instance of the masculinity that arises from consistently treating boys as prizes and girls as burdens. Laapataa Ladies presents us with a more villainous instance: The bridegroom Pradeep (Bhaskar Jha), who’s killed off one wife already and only married a second for a dowry — and a free slave. Because it’s a comedy, we don’t need to weep or rage about the fate of the unknown dead woman. But because it’s a comedy, we are also offered the satisfaction of seeing this vile man robbed of social power legally — and that too, by the police he thinks are on his side.

What the ladies want

The draw of Laapataa Ladies lies in its sweetly optimistic depiction of a bitterly contested milieu — perhaps deliberate in times when the Hindi belt seems like a war zone. There are moments when Rao successfully tempers her Doordarshan nostalgia and her almost teacherly tone with self-reflexive humour —- like when one character asks another if she’s been watching too much Krishi Darshan. But try as the film might to laugh at it, it is in the state — embodied in Ravi Kishen’s eventually law-abiding policeman — that Laapataa Ladies’ optimism really resides. However fictional, Rao’s film is a throwback to the memory of a more benevolent, constitutionally-bound state — as well as an unspoken plea for its continuation.

Trisha Gupta is a Delhi-based writer and critic, and Professor of Practice at the Jindal School of Journalism and Communication